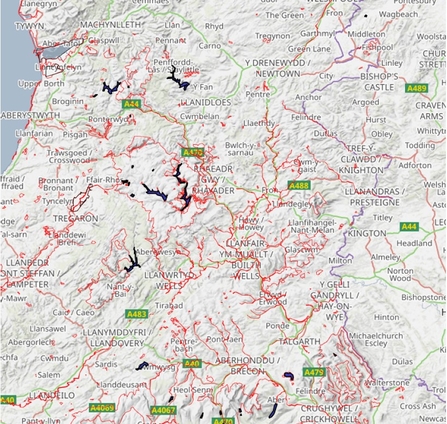

When someone refers to “the lungs of the Earth”, what comes to mind? It’s likely that what comes to mind are forests, and even jungles much further afield than Radnorshire. Of course, the leafy green expanses around the globe are vital for processing carbon and providing us oxygen, and we continue to champion their preservation, recovery and connectivity. However, there’s another precious element that once added to a landscape, creates opportunity for our planet to take ‘breaths’ that help us all out in the race against climate change and biodiversity loss.

So, it is no wonder that within the topic of land management and habitat restoration, some key players get a lot of attention; the inland stretches of squelch such as wetlands, flooded woodlands, the bogs, mires, ponds and lakes. Alongside the Wildlife Trusts, many conservation organisations often advocate for the restoration and expansion of wet habitats. This is not by any means only for goals on biodiversity increase and nature’s recovery. The win-win of it is that water dominant ecosystems rich in species across taxa can be top powerhouses of sequestering carbon from our atmosphere. You could in fact, name them the true ‘lungs’ of the Earth.